Research

Mercury’s heart of Iron

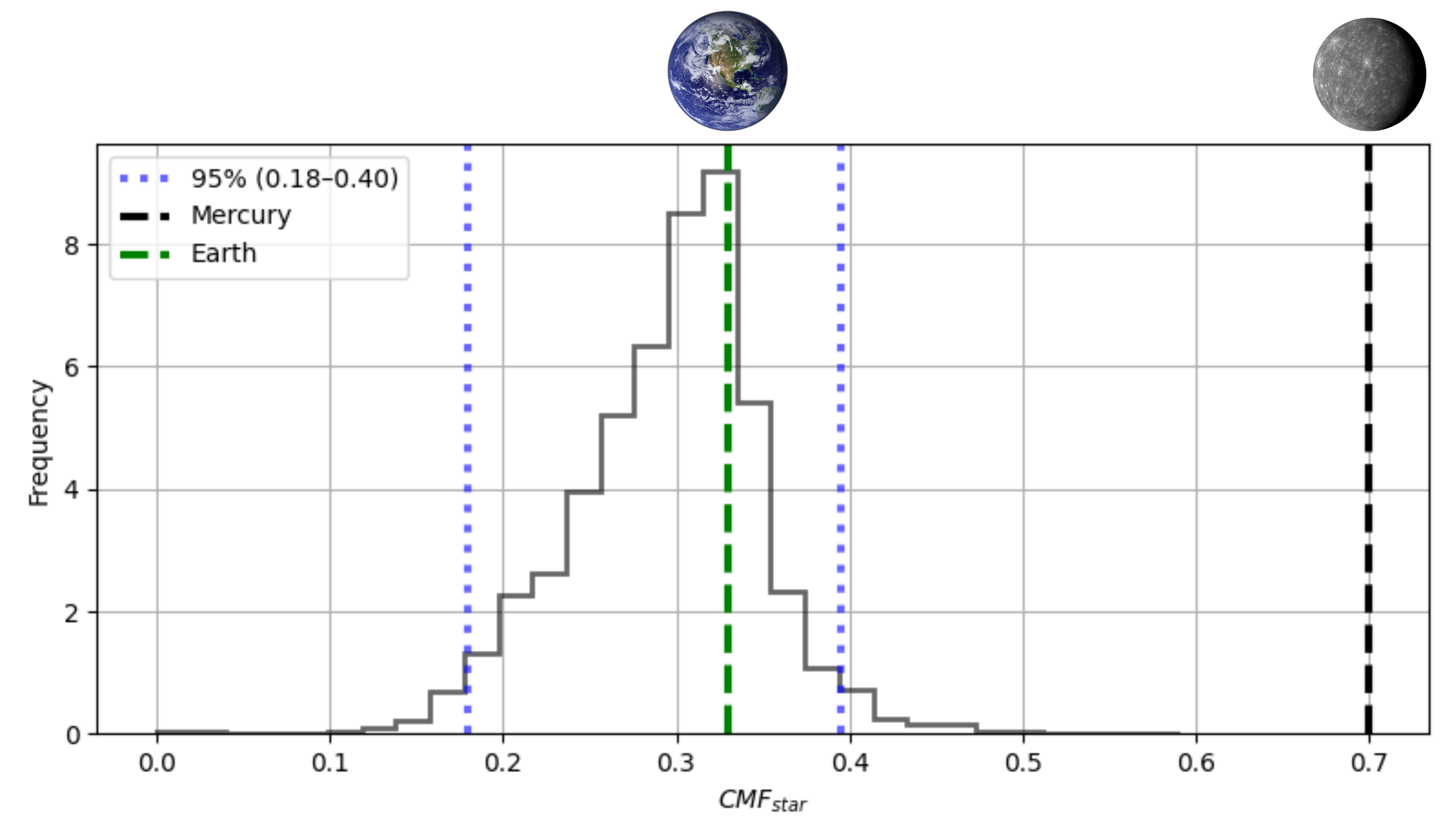

Mercury is an oddball in the solar system due to its high core mass fraction (~0.7), in contrast to the other rocky planets, which have core mass fractions (CMFs) of around 0.3. How Mercury ended up with such a large core remains a mystery. One possible theory is that a giant impact stripped away the outer mantle layers from a proto-Mercury, leaving it with a large core mass fraction. However, the probability of a single giant impact with enough energy to remove that much material is very low. Moreover, observations of volatiles on Mercury’s surface challenge this scenario.

With more and more exoplanets being detected every day, a growing number of observations have revealed extremely high-density exoplanets. Models of planetary interiors suggest that these planets have Mercury-like compositions; however, they are significantly more massive and exhibit a variety of orbital architectures.

Consequently, understanding the formation of Mercury and exo-Mercuries is essential to understanding planet formation as a whole. In my research, I explore questions such as: Is it possible to form a Mercury-like planet through a single giant impact? Can it instead be produced through multiple erosive impacts during the planetesimal stage? How does a star’s metallicity influence planetary compositions? In what ways do differentiation processes shape a planet’s final composition? And what role does the initial CMF distribution (during the planetesimal phase) play?

We do N-body simulations using the state-of-the-art N-body code rebound [7] to study the evolution of rocky planets during the planetesimal phase. We start with a disk made of small planetesimals (almost Moon mass) and bigger planetary embryos (~ Mars mass). [1] At this point, all rocky bodies are differentiated. Total disk mass is derived based on the minimum mass solar nebula, and the edges of the disk are based on the solar system rocky planet orbits. Using a fragmentation module [2] we track the composition of bodies during this collision phase. The collision outcome is determined based on the impact energy [3], which can be erosive producing fragments, accretive, merging or an elastic bounce. We conduct 30 Simulations and integrate for 300 Myrs.

We perform N-body simulations using the state-of-the-art REBOUND N-body code [7] to study the evolution of rocky planets during the planetesimal phase. We initialize the simulations with a disk composed of small planetesimals (roughly Moon-mass) and larger planetary embryos (~Mars-mass) [1]. At this stage, all rocky bodies are assumed to be differentiated. The total disk mass is based on the minimum-mass solar nebula, and the radial extent of the disk corresponds to the orbital range of the solar system’s rocky planets.

Using a fragmentation module [2], we track the compositional evolution of bodies throughout the collisional phase. Collision outcomes are determined based on impact energy [3], and can be erosive (producing fragments), accretive, merging, or elastic bounce. We have conducted 30 simulations so far, each integrated for 300 million years.

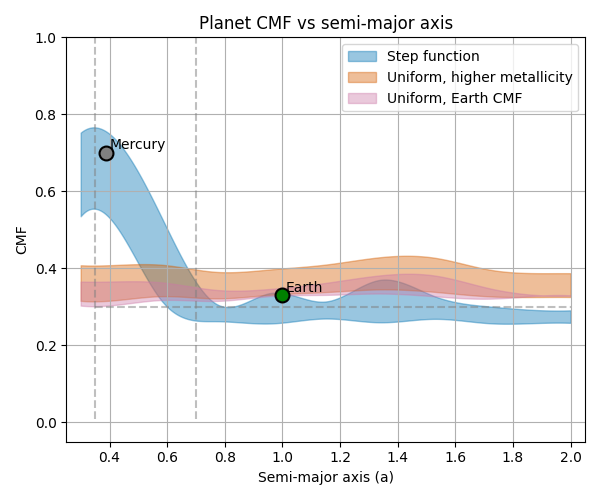

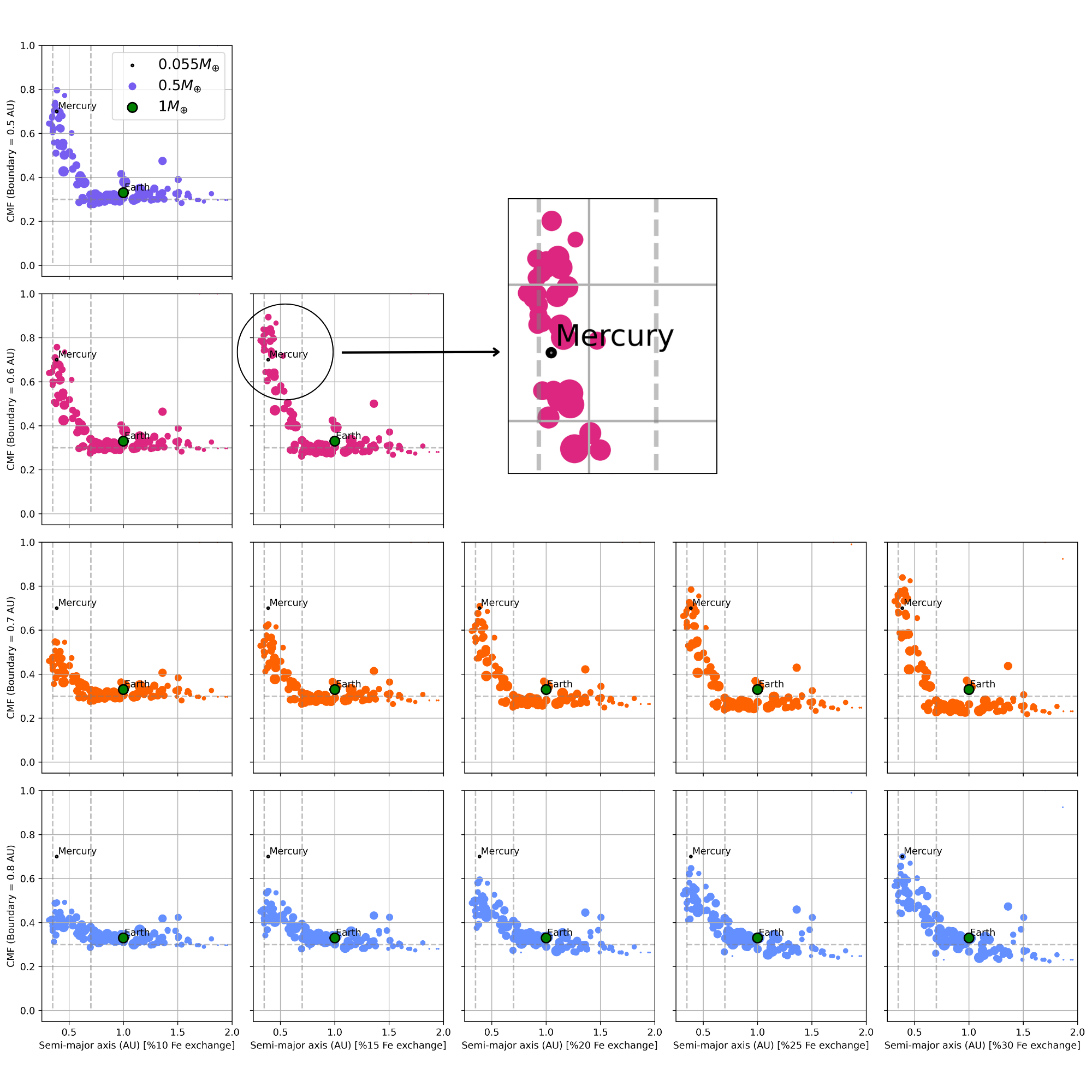

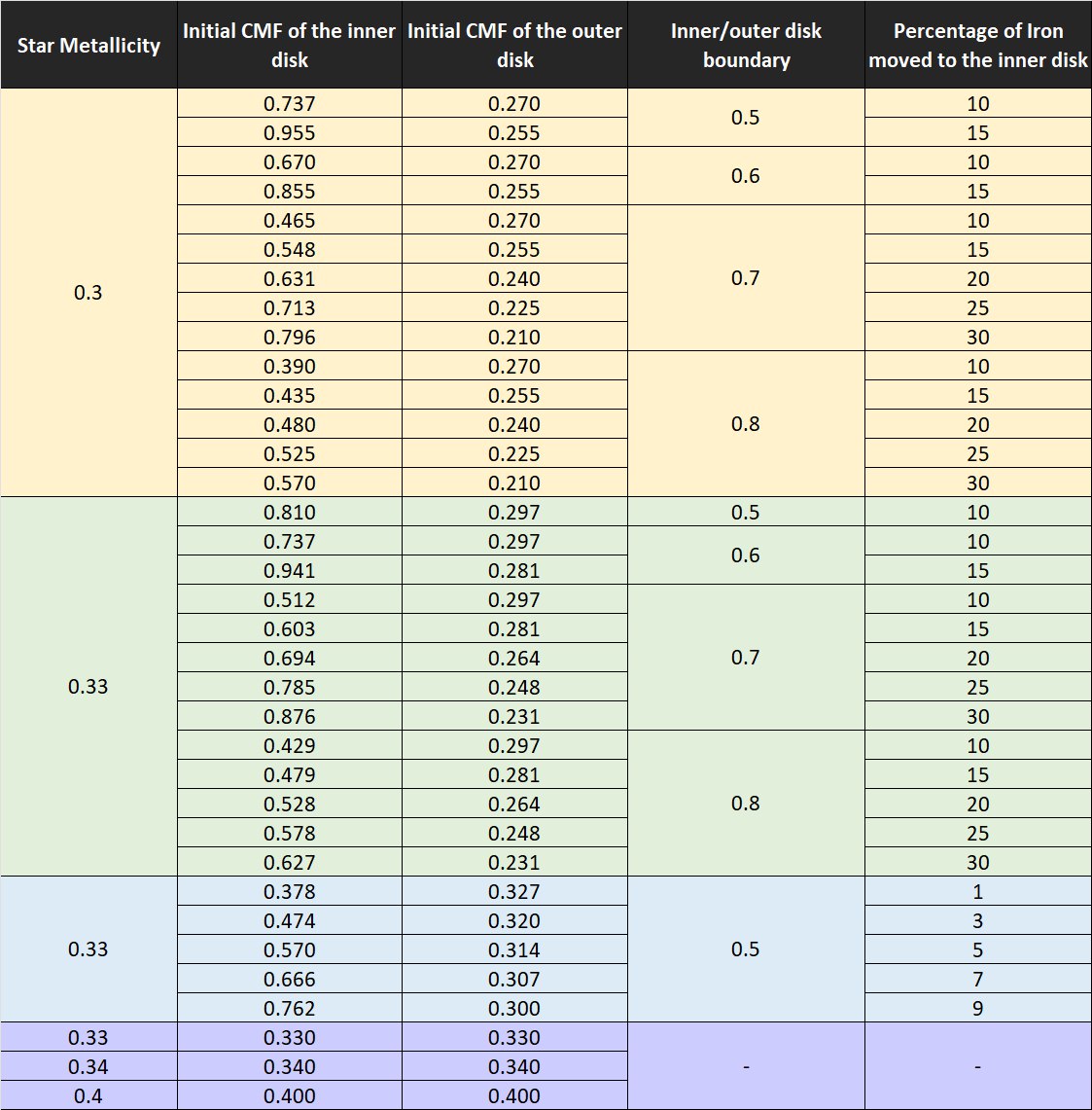

To study the effects of initial disk composition (initial core mass fraction distributions), we test the following cases: 1) Uniform CMF distribution based on solar metallicity. 2) Uniform distribution based on higher-metallicity stars. 3) Step-function CMF distribution, keeping the total iron mass constant but bringing more iron to the inner disk (high CMF inner disk and low CMF outer disk).

Our results indicate that without having an Iron-rich region, it is not possible to make a Mercury-like planet and Earth-like planets in the same system.

The table below demonstrates our different choices of initial CMF distributions.

Previous research has suggested some processes that lead to iron-enrichment of the inner disk, some of which include magnetic and thermal differentiation [5][6]. Our future steps involve investigating the astrophysical phenomena that favor an iron-rich inner disk during the planetesimal phase. We also aim to study the probability of forming exo-Mercuries; however, to do so, we need different disk models, as most exo-Mercuries are much more massive than Mercury (a few Earth masses) and reside in closer orbits to their host star (orbital periods on the order of a few days). A more massive disk and a closer inner edge introduce tremendous computational costs into the simulations, as they increase the number of particles and reduce the time step. As fragmentation occurs, more mass results in more bodies being added to the simulation, making the runtime longer. Possible solutions include using a GPU-based N-body code or faster integrators, such as TRACE [8]. TRACE supports adding fragments in its newest update and is expected to be orders of magnitude faster than the current integrator used (MERCURIUS).

References

- Chambers, J. et al. (2013). Icarus, 224, 43.

- Childs, A. & Steffen, J. (2022). Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 511, 1848.

- Leinhardt, Z. M. & Stewart, S. T. (2011). Astrophysical Journal, 745, 79.

- Hyodo, R. et al. (2020). Icarus, 354, 114064.

- Kruss, M. & Wurm, G. (2018). Astrophysical Journal, 869, 45.

- Wurm, G. (2018). Geosciences, 8, 310.

- Rein, H. & Liu, S.-F. (2011). Astronomy & Astrophysics, 537, A128.

- Lu, T., Hernandez, D. M., & Rein, H. 2024, MNRAS, 533, 3708, https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stae1982

- Hinkel, N. R., & Burger, D. 2017, arXiv:1712.04944